What this Article is About

This article examines the root causes of youth violence and school shootings through the lens of the author’s experience working with violent offenders and broader societal trends. It argues that these tragedies stem from systemic social fractures, including chronic trauma, poverty, loneliness, and alienation, rather than individual pathology. The author draws on psychological research and compares modern Western individualistic society with Islamic social architecture, suggesting that the latter’s emphasis on communal belonging, purpose, and moral accountability offers an alternative civilizational model that could prevent such violence by addressing the fundamental human need for connection and meaning.

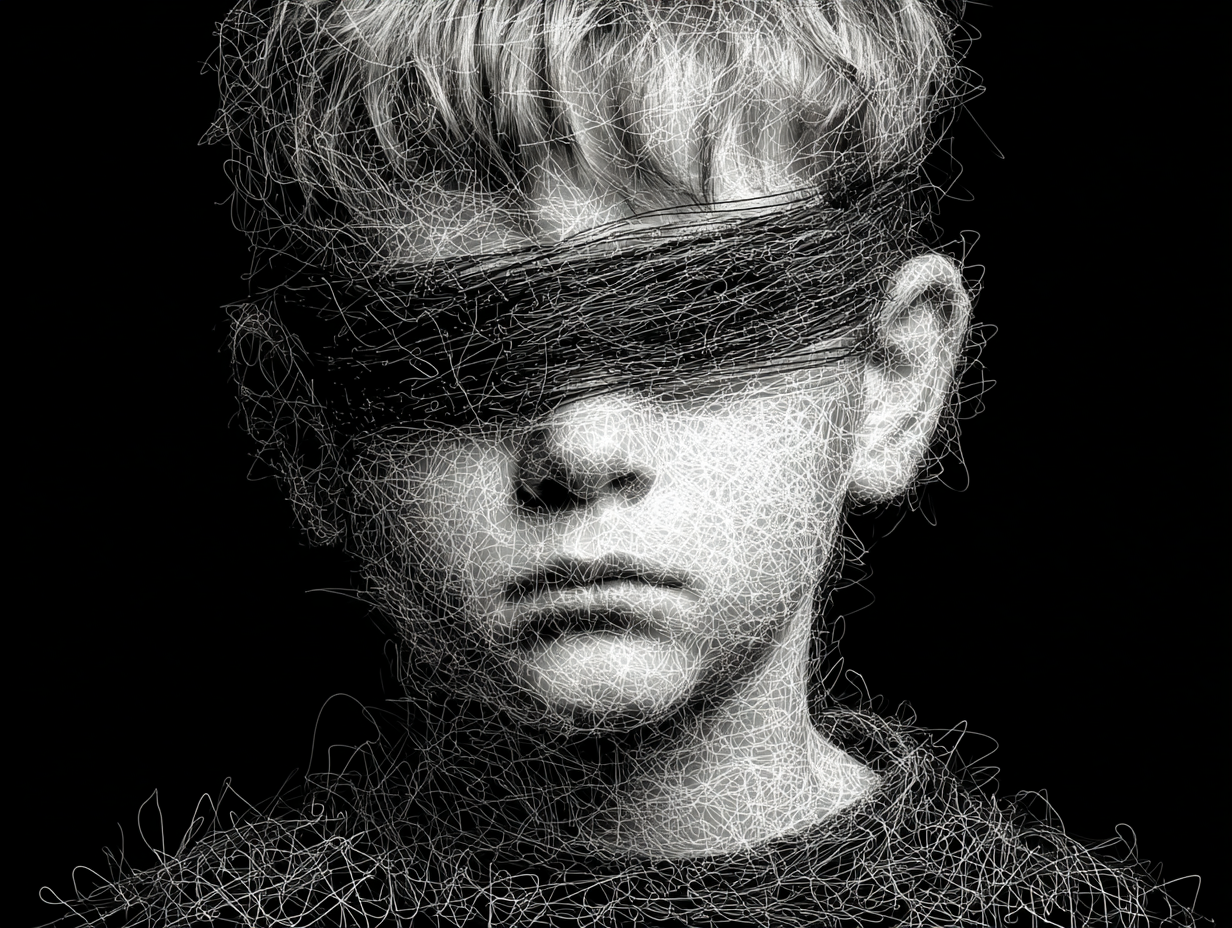

Behind Locked Doors: What the Files Revealed

I once worked in a group home for underage violent offenders. I once worked in a group home for underage violent offenders. One night, unsettled by the fact that these boys appeared outwardly normal yet had committed serious acts – rape, theft, violent assault – before the age of sixteen, I sat alone in the office and began going through their files. Psychological assessments. Social histories. Court documents. Family reports. Page after page of trauma. The patterns were not subtle. The same themes kept appearing: low socioeconomic backgrounds, broken or unstable families, chronic neglect, exposure to violence, inconsistent schooling, addiction in the home, and untreated mental illness. These were not cartoon villains. They were children shaped by chaos.

At the time, that work felt extreme, enclosed within locked doors. But in the years since, I have watched from the outside as the kind of pain I saw behind those files has surfaced in broader social trends. The themes that once marked only the hardest cases in residential care – disconnection, humiliation, absence of belonging – have begun to show up in places once assumed safe: ordinary schools, everyday neighbourhoods, cultures proud of their civility.

When Even “Peaceful” Societies Fracture

This came to mind more clearly when I read of the recent school shooting in Canada, a country long fabled for peace, restraint, and quiet civic order. The attack shattered that mythology. Reports described students and staff running for safety, families waiting in agony for updates, and a community struggling to comprehend how such violence could erupt in a place so often held up as stable and calm. Canada’s global image has frequently contrasted itself with the United States on issues of gun violence, yet this tragedy underscored that alienation, youth despair, and the possibility of catastrophic rupture are not confined to national branding. The details of the victims – young lives interrupted, parents left grieving – mirror the same unbearable pattern seen in the US: a moment of explosive violence born out of a long, unseen story. The setting may differ. The human fragility does not.

From Sanctuaries of Learning to Spaces of Anticipated Threat

When I reflect back, what I saw in those group home files was not an isolated phenomenon. The societal fault lines that shaped those children have widened. Across the United States, schools that once stood as spaces of learning and community are now adapting security measures that resemble defences rather than welcome zones. Active-shooter drills have become routine. Metal detectors have been installed in hallways. Armed officers are stationed in cafeterias. According to data from the National Center for Education Statistics, the majority of U.S. public high schools report having sworn law enforcement officers present on campus at least weekly (https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d21/tables/dt21_233.70.asp). What was once exceptional has become structural. This shift reflects not only fear of violence but a deeper societal anxiety – a recognition that the conditions creating violent behaviour are not contained but diffuse.

A Culture That Calls Itself “Normal”

When I think back to those case files, I hear Dr. Gabor Maté’s argument in The Myth of Normal with new clarity. He writes that what we call “normal” in modern society is often profoundly unhealthy. Many psychological disorders, he argues, are not random defects but adaptations to environments that fail to meet core human needs for attachment and safety. Trauma is not simply what happens to a child. It is what happens inside a child when they must adapt to chronic emotional misattunement, instability, or threat.

In hyper-individualistic, capitalist societies, children are raised inside systems organized around competition, productivity, and performance. Parents are stretched thin by economic pressure. Economic inequality has widened for decades, with U.S. Census Bureau data showing a long-term increase in income disparity since the 1970s. In poorer communities, housing insecurity, food instability, and lack of access to mental health care compound daily stress. The landmark Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) studies conducted by the CDC and Kaiser Permanente demonstrate a strong, graded relationship between childhood adversity and later mental health and behavioural problems (https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/aces/index.html).