A Civilizational Question, Not Just a Policy Problem

If Dr. Maté is right, then what we are witnessing is not simply a series of individual pathologies but the extreme edge of systemic fracture. A society organized around competition, weakened community bonds, eroded social care for the poor, epidemic loneliness, militarized school environments, and mythologies of redemptive violence should not be shocked when some children collapse under the weight.

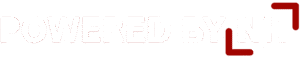

The question is not only why some kids pick up guns. The deeper question is what kind of society produces so many children who feel so profoundly alone that violence appears, however distortedly, as a path to being seen.

And this is where an alternative civilizational model matters.

Islam does not begin with the isolated individual. It begins with belonging. The child is not an economic unit or a future competitor. The child is an amanah – a trust. The Qur’an describes human beings as created with purpose, as servants of Allah ﷻ and vicegerents (khulafa’) on earth. A child raised within that worldview is not floating in a meaningless universe, scrambling for validation. He or she is part of a moral cosmos, accountable, dignified, and known by the Creator.

Islamic social architecture is historically centred on extended families, kinship obligations, and communal responsibility. Care for the poor was not outsourced to charity alone but embedded structurally through zakat, waqf endowments, and communal institutions. The elderly were not warehoused. Orphans were not invisible. The Prophet ﷺ repeatedly emphasized mercy toward children and warned against the hardness of heart. In an authentic hadith, he said, “He is not one of us who does not show mercy to our young and respect to our elders” (Tirmidhi).

In such a framework, a child grows up knowing where he belongs. He belongs to a family network larger than himself. He belongs to a community that prays together. He belongs to a moral order in which suffering has meaning and life has accountability. He is not told that worth comes from domination or spectacle. He is told that true strength is restraint, service, and taqwa.

None of this romanticizes history or denies that Muslim societies have flaws. But the foundational vision is different. It nurtures identity not through grievance but through purpose. It anchors dignity not in notoriety but in servitude to Allah ﷻ. It embeds social care structurally rather than leaving families alone under economic strain.

A child who feels he has a place in the universe – as a servant of God, as part of an Ummah, as someone entrusted with a mission – does not need violence to feel visible.

If we are serious about preventing future tragedies, we must think beyond policy adjustments. We must ask what kind of civilization we are building, and whether it nourishes or starves the souls of its children.